Translation software encompasses an array of tools and resources that help individuals translate written or spoken content from one language into another.

Today, there are several types of translation software on the market — from machine translation software to computer-assisted translation tools.

If you want to learn how to become a better technical writer, you need to understand the different types of translation software that exist today and how they can best be leveraged by technical writers and multilingual communicators.

Translation Memory

Translation memory (TM) software is one of the older types of software used by translators to support translation work. The only software in the translator’s toolkit that is older are word processors and early versions of terminology management software. Nearly forty years ago, the first versions of translation memory software were created to make translators more productive.

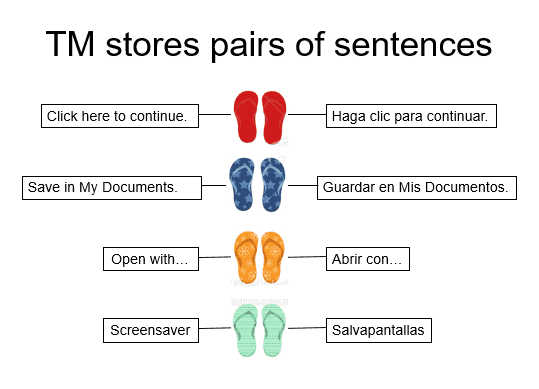

Translation memory tools, as the name suggests, help translators recall what translations may already exist for text that they are translating. The concept is simple: The translation memory software stores original sentences along with their corresponding translation in a database, which can then recall them for use whenever the translator encounters the same or similar sentences. The translator then has the option to reuse a match that they get from the translation memory database or offer a different translation.

Figure 1 How translation databases store original and translated sentences

While working, the translator can preview any matches that may be in the translation memory database.

Figure 2 MadCap Lingo's translation grid

MadCap Lingo is a translation memory tool that works in this fashion, as shown in the example above. All translation memory tools rely on importing an original document into the software. These applications natively support multiple file types — DOCX, XSLX, TXT, HTML, XML, etc. MadCap Lingo has the benefit of integrating with MadCap Flare and can import whole Flare projects that include all file types used by Flare.

RELATED: Learn how to translate a Word document with MadCap Lingo.

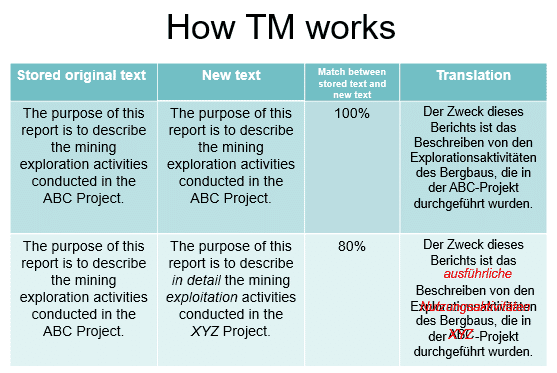

Within this “translation grid,” the translator can edit the proposed translations or replace the whole software translation if they choose. They can also see the percentage match of each proposed translation. A 100% match indicates that the sentence being matched is the same as the one previously translated. A 101% match is known as a “context match”. This means that the translated text matches 100% and the sentences that precede and follow it are the same as in a previous translation.

Figure 3 How translation segment matching works

An average translator can translate approximately 2500 words per day without a translation memory. However, with a reliable TM that contains high-quality content, the same translator can be five or six times more productive.

One important aspect of translation memory tools is that the software is proposing translations that a human translator has previously created. The goal is to make it easier and faster for a translator to recycle translated content, which in many scenarios makes sense since so much content being authored is recycled or revised. MadCap Flare is designed to make “write once, use often” a best practice for authors. Translation memory makes it possible to match that recycled content to existing translation in a highly automated and efficient manner.

Terminology Management Software

A complimentary type of software to translation memory is terminology management software. Managing terminology is a critical facet of a quality-focused translation process. Even SMEs debate terminology both in the source language and in the target. Proactively managing terminology avoids inefficiency during translation and assures consistent, accurate translation in the target language that’s in line with corporate standards.

A terminology database (or termbase) enables a more robust method for tracking terminology standards and preferences, including metadata about terms, their origins, and how they should be used. These systems are generally interoperable between different software platforms either via data exchange standards such as TBX (an XML standard) or other generic methods like CSV. There are also web-based terminology portals that can support the development of custom termbases.

A termbase is different from a translation memory database, with the former providing a foundation for the latter. To learn more about how these two tools work together, please see Why You Need Both Translation Memory and Termbases.

Machine Translation

The other leading area of translation software is machine translation. Machine translation is the creation of translated content by a computer software system. This software does not require human intervention to create a translation—in theory.

Machine translation software comes in multiple flavors. The oldest iterations which arose as early as the 1960s consisted of rules-based systems that attempted to predict the structure of a translation in a specific language based on the grammatical rules of both the source language and target language. These rules combined with electronic dictionaries generated “word-by-word” translations that were not very fluent and prone to error due to the rigid nature of how the translation was generated.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, statistical machine translation became the prevailing technology. These systems relied on large datasets and statistical calculations to guide how words and phrases are combined to generate a translation. They proved to be far more useful than rules-based systems, creating content that was more fluent. Alas, these systems also proved to have significant limitations, which required lots of human intervention, but by around 2010, results had improved enough that a net productivity gain for translators using these systems emerged.

In the last five years, statistical systems have increasingly been supplanted by neural machine translation (NMT) systems, which utilize neural network technology to predict which words a translation will use. These systems have proven to be far superior to legacy systems, resulting in far more fluent and usable translations, requiring far less human effort to render useful translations. In some subject matter areas, neural machine translations are so good that readers have trouble discerning between machine- versus human-generated translations. However, NMT is not a panacea, and it does have its limitations. Overall, it is still a tool that is best wielded by professional translators to increase productivity and control costs.

The Emerging Content Stream

Currently, well-equipped translation providers rely on all the above tools to create translations faster, better and cheaper. With a high-quality translation memory, a well-populated termbase, and a subject matter-trained neural machine translation engine, translators can create content faster and more reliably than ever. Lowering cost is great for corporate bottom lines, but more importantly, it stretches corporate budgets, allowing companies to translate more than they have before, resulting in excellent customer satisfaction and more opportunity in outside markets.

Translation providers now work in a content stream that is a mix of human translation TM matches, proposed machine-translated content, which close gaps in what the translation memory database may not contain, and highly accurate subject-matter-specific terminology that meets the expectations of the target audience.By no means are these all the software tools used by translation providers, but regarding how translated content is generated, these are the top professional translation management systems of the trade.