This guest blog post was written by Homer Christensen, an Information Architect, MadSkills consultant, and an award-winning tech writer and UX designer. His client list includes Nestlé, Microsoft, Ellie Mae, Conga, and the State of California. When not writing or coding, he’ll likely be bikepacking, winemaking, or enjoying his permaculture garden.

We’ve all been assigned mandatory training that felt more like work (the dull kind) than learning. I admit that I’m guilty of clicking through screens in a policy elearning course to quickly take the quiz, check that Development Plan box, and get on with my real work.

But what if more care was given to the user experience design of the training, so that it was mentally engaging, maybe bordering on fun, visually stimulating, and designed with me in mind?

Learning Experience Design, commonly called LXD, might offer a better approach.

What is Learning Experience Design?

LXD is a fairly new branch of learning and development, developed in 2007 by Niels Floor, a professor at Avans University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. He sums it up this way: “Learning experience design is the process of creating learning experiences that enable the learner to achieve the desired learning outcome in a human centered and goal oriented way.”

At its simplest, it focuses learning resources directly on the experience, rather than, say, a

more traditional method where an instructor lectures a class on a subject or a learner reads

and completes an exercise to prove their knowledge. LXD emphasizes effective learning, as opposed to teaching or instructing. But what constitutes an experience? Lxd.org states that any experience or situation that occurs over time and leaves an impression can be considered a learning experience. These learning experiences aren’t limited to the classroom or website, but instead can happen anywhere.

That’s a fairly broad definition, and it’d seem that any experience is okay, even the not-so good ones. Nope. Dull experiences can be quickly forgotten and negative experiences have a

limited lifespan, especially when any punishment is removed. So, what would push one

experience over another into a transformative learning experience?

The key, as Floor points out, is that the experiences that a learning experience designer creates are human centered and goal-oriented. This means that the LX designer must discover what motivates learners to facilitate that natural desire to learn. Of course, not every person shares the same intrinsic motivation, so an LX designer often employs interviews and direct behavior observation to create a learner persona that helps describe their targeted groups of learners and their motivations.

Likewise, the designer needs to uncover the goals that best support the learner so that achieving those goals results in a successful learning experience that is meaningful and has a good chance of being retained. Often, the method the designer uses to achieve those goals will determine the medium or technology chosen to deliver the experience.

Floor makes the comparison that a traditional Instructional Designer is like a scientist, while an LX designer is an artist. I find that a bit precious and self-congratulatory. Good design always has elements of each, and you’ll find both types of designers using cognitive theory to ensure their work is sound. Their approach, however, is a bit different.

The Learning Experience Design Process

In the world of traditional Instructional Design, a designer is often presented with a problem statement. Support tickets are increasing (as are costs) around a particular process; finance requests a training course to reduce employee travel expenses. Or perhaps a new product version is dropping and an ID is asked to update existing courseware.

In each case, the ID would perform an analysis to determine the scope of the knowledge gap, and design and develop a course or short training to close it. Then the ID tests, refines, and implements the design, and then measures the success of the training.

LXD follows a vaguely similar process, but with some important differences.

An LX designer starts with a question. In many ways, it seems like LXD questions are bigger, fuzzier, and more broad than those probing a knowledge gap, even if they both address the same gap. Sometimes, the obvious question might not be the most relevant one to ask, and designers often spend some time here to discover the question to ask. LXD questions might sound like this:

- How do we help people manage their money to live debt-free?

- How can we identify, avoid, and report phishing emails?

- How can we recognize an implicit bias we might have and understand how it affects our co-workers?

Just as in traditional instructional design, the LX designer jumps right into research. The designer looks at the learners that the primary question targets and determines their motivations and interests that might create good learning outcomes. Typically this involves one-to-one interviews, focus groups, and other hands-on research to gain a deep understanding for an appropriate learning solution. Likewise, the designer also researches the stated outcome. What behaviors would determine that the learners achieved the outcome?

The question about identifying phishing emails, for instance, would apply to all employees and—notwithstanding the shame, embarrassment, or financial cost of being responsible for data loss at work—each person also has a motivation to recognize a ransomware or malware attempt and block it to protect their personal financial data.

You’d know that the employees achieved their learning outcomes if all phishing emails that were sent to the email server were reported as such and not opened. (A mildly devious IT team might send some sterile phishing emails to users after the course to see if employees can identify and report them. If so, a nice Good Job! message can reinforce the learning.)

Once you have a good handle on the learner groups and the outcomes, you can brainstorm ideas as to how to craft experiences that interest your learners and create an ‘Aha!’ moment where they learn without tedium. How does your audience interact with the world and each other? What technologies are they familiar with and use frequently?

Being as it is centered on experiences, the types of learning you’ll design will be more experiential. LX designers often make use of gaming theory, videos, and quizzes (especially for remote or asynchronous learning), as well as collaborative exercises such as role-playing, discussions, brainstorming sessions, and other activities that can involve each of the learners in a group.

More on eLearning Design: What is blended learning?

A game might be a good approach to discovering all of the nefarious ways that scammers try to trick users into falling prey. This type of exercise can replicate many of the techniques used in the real world of email without the consequence of a bad choice.

More than likely, the LX designer will include more than one type of experience to make the learning more well-rounded and complete. But don’t think that an experience can’t include a lecture or discussion by an instructor; LXD encourages free-thinking to discover and identify the best way to deliver information. The ethos discourages the idea that one kind of experience is best for a certain type of learning; rather it encourages the designer to stay flexible and consider which experiences would best involve and encourage learning among the particular audience they might be targeting.

For instance, not all visuals are videos. An infographic might just be perfect for conveying the costs of phishing emails and the impact it has on businesses around the world. Memes are ubiquitous and sometimes quite effective at messaging.

Before going live with a course, a good LX designer will test the experiences they’ve put together with a target group of the intended audience, gather the comments and reactions, and perform knowledge checks to determine the effectiveness of the training. That’s not unique to LXD, of course; that feedback loop is essential to the development of any successful training.

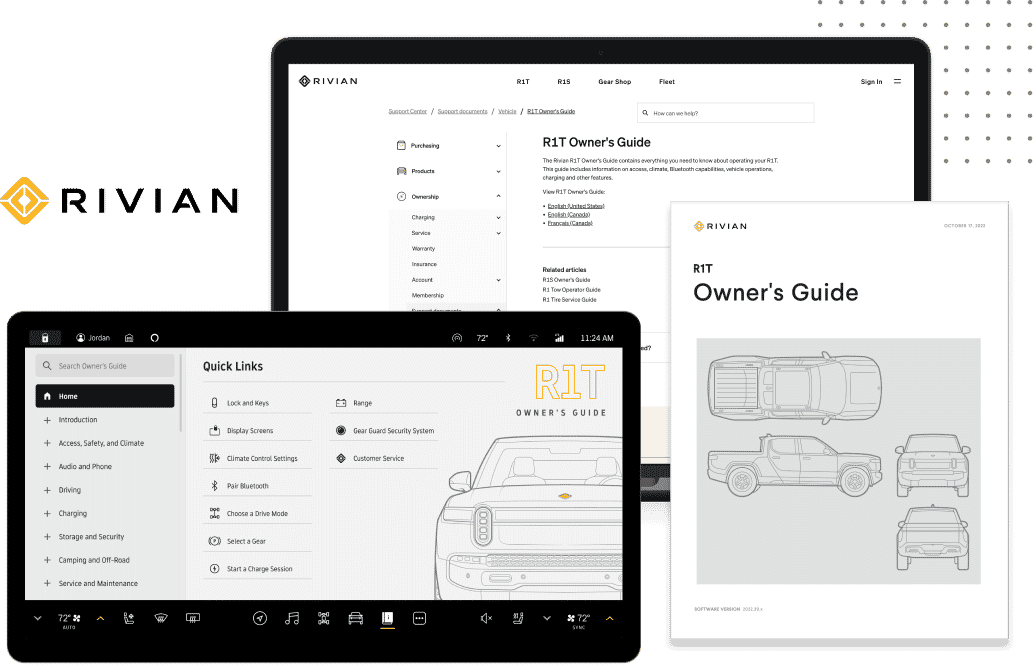

Applying LXD to Your MadCap Flare Projects

If you want to improve the learning experience for a new or existing MadCap Flare project, keep in mind that LXD does take a certain amount of up-front time researching your audience and brainstorming activities or experiences that best deliver the training.

That doesn’t mean you need to scrap an existing project and start over, nor does it mean that you shouldn’t even consider it due to time constraints. You might find it helpful to look for those marginal gains that you can get with fixing the slow or ineffective parts of your training.

Find a selection of trainees who have taken the training and ask them for their feelings about different parts of the training. Which did they find slow, boring, or confusing? Which worked (equally as important!) and shouldn’t be changed? Interview them to discover why, what types of experience they find fun or engaging. Consider a gentle test to determine what they retained. If they’re a good representative segment of your audience, you might be able to apply those findings as a solid start. Otherwise, interview prospective audience members to learn more about them. And then brainstorm activities to design the most effective experiences.

Because Flare uses standard web technologies, you can use third-party tools to develop quizzes, videos, walkthroughs, or other activities and fold them into your training, either as a link or embedded object. Animations, clever uses of typography, and other built-in CSS and web design elements can also work together to heighten the effectiveness and increase engagement of your content. This gives you the ability to incrementally add targeted experiences and validate their effectiveness.

After all, our goal as designers and developers of learning content is to create materials that provide the best experience for our learners, so that they leave with heads full of information and smiles on their faces.